What is the Dragoman Challenge?

Elvin Abbasbeyli and Sylvie Nossereau chat about their multilingual journey of discovery about early colleagues from the Ottoman Empire

Also available in French

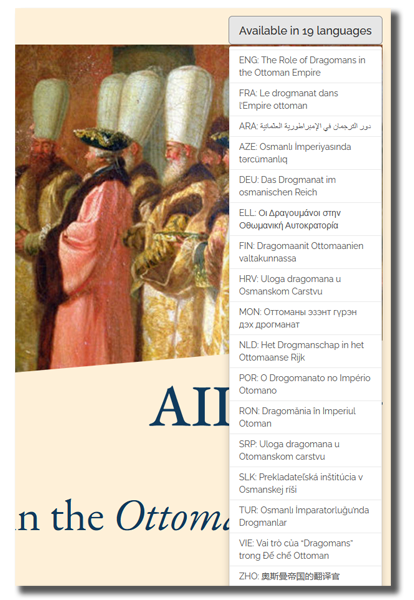

Elvin Abbasbeyli’s essay, The Role of Dragomans in the Ottoman Empire, is the most translated article of the AIIC blog, rendered in 34 languages – 19 of which have been added to the blog – at the moment of this publication. Thanks to Sylvie Nossereau’s inspiration to launch the Dragoman Challenge and invite colleagues to furnish more translations, you can now discover this fascinating account of our early forebears in everything from Dari to Swahili, from Vietnamese to Romanian, from Mongolian to Korean, and, of course, in Turkish. And the list continues to grow…

In this interview Elvin and Sylvie discuss the essay and how its multilingual proliferation came about.

How did you become interested in the dragomans?

Elvin: I was casting about for a research topic for my PhD in Turkish and translation studies when I came across an article written in Turkish, devoted to the history of translation in Turkey and which provided a brief overview of the dragomans of the Ottoman Empire.

I asked my thesis director if I could research these historical figures, even if I didn’t know exactly what my thesis topic would be. He suggested that I focus on the Treaty of Kücük Kaynarca, which was signed in 1774 between the Ottoman and Russian Empires.

After some preliminary research, I decided to delve into the translation and terminological analysis of the three existing versions of the treaty (the original version, in Italian) and the two translations thereof (Ottoman Turkish and Russian) and to talk about the translators: the Dragomans.

You must have discovered some fascinating things during your research!

Elvin: My dragoman research was a seven-year endeavour, and it allowed me to discover these forefathers of translation and interpretation in the Ottoman Empire and, later, in Turkey. I also learned so many other things, more than I have time to tell you about during this interview, but one thing that really stood out for me was the translation and interpretation techniques used by the dragomans.

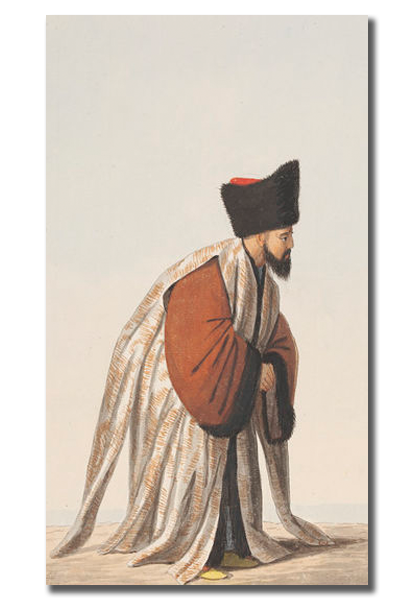

As I wrote in my article that gave rise to the Dragoman Challenge, there were schools created by Westerners, but the dragomans of the sultan did not necessarily attend these schools; they learned by doing. And without even realizing it, they acquired techniques that resemble what we would call today liaison interpretation—I wouldn’t call it consecutive interpreting because, despite the existence of paintings that clearly depict the chief dragoman beside the Ottoman sultan, they did not actually take notes the way we do today.

After comparing the original treaty with the two translated versions, I realized that they were also versed in translation techniques and processes that we have names for today (borrowing, calque, literal translation, transposition, equivalent, adaptation, modulation).

We should keep in mind that there were no translation schools at the time; knowledge was handed down from one generation to the next, since this was a family profession. Some families served the Ottoman sultans for many years.

It wasn’t until 1821 that the Translation Office (Tercüme Odası) was founded in the Ottoman Empire. This was also the year of the Greek revolution, which the Ottomans saw as an uprising. The Ottoman dragomans were often Greek, and therefore the sultan sought Muslim dragomans who would be loyal to him.

This Translation Office was thus tasked with training government officials who were fluent in foreign languages, future dragomans of the Imperial Council (Divan)¸ and those posted to Ottoman missions abroad. The Office was also responsible for translating French publications into Ottoman Turkish.

So we can see that dragomans were practicing translation and interpretation well before the creation of the Office, which makes their profession all the more impressive.

Why did you translate this article into several languages?

Elvin: I had originally written it so as to make it more accessible to AIIC blog readers. I wrote it in French, and then I decided to translate it into Azerbaijani. That’s when I discovered that it’s not easy to translate your own work!

I then asked some of my colleagues to translate it into English and Turkish. A few years later, other translations (Romanian, Slovakian, Mandarin, Mongolian and Korean) were done, either by my colleagues or my students. Every time a new translation was published, I shared it on Facebook.

Following the publication of the Korean version, Sylvie Nossereau had the brilliant idea of launching the Dragoman Challenge, with a view to having my article translated into as many languages as possible in order to pay tribute to these pioneers of our profession. That’s where it all started.

Sylvie: I also see it as a way of increasing the visibility of AIIC, by piquing our colleagues’ curiosity about a lesser-known chapter in the history of these language professions.

We can learn so much from our past, because it allows us to draw certain parallels with the present and put things in perspective. For example, it is now universally acknowledged that Nuremberg was a turning point in our profession, thanks to the use of simultaneous interpretation, even though many great consécutivistes were at first resistant to this new mode.

We are seeing similar resistance to the rise of distance interpretation, but Nuremberg reminds us that we must be willing to adapt, because we are now confronted with yet another tectonic shift in our profession, that of rising to new technological challenges.

What can we learn from our forefathers the dragomans? Translation and interpretation are perhaps less prestigious professions nowadays than they were then, but they are also, without a doubt, less dangerous, not to mention accessible to all social classes, and to… women! So perhaps the good old days weren’t so good after all?

This project is also a symbolic means of forging ties with colleagues, and perhaps encouraging some of them to get more involved in AIIC.

We began by reaching out to our personal contacts, and the publication of the various translations on social media caused a ripple effect, with colleagues from other language associations expressing their interest.

The translators, all of whom worked on a volunteer basis, reported enjoying the Dragoman Challenge. This initiative brought translators and interpreters closer together and showcased all languages on an equal footing, since some of the translations are in languages that are seldom or never used in international organizations, languages of lesser diffusion, and regional languages.

Appropriately enough, our project also took place in 2019, the International Year of Indigenous Languages as declared by the UN.

And last but not least, since the pandemic has made travel well-nigh impossible, these translations provide us with a different kind of escape.

Would the dragomans of the Ottoman have considered us their colleagues?

Elvin: Even though we don’t travel on horseback, wear silk arments, have sabres dangling from our belts, or employ dozens of servants, like the dragomans did, they would nonetheless have considered us their colleagues, because we share the same mission: to serve as a bridge between cultures.

What would the dragomans of the Ottoman Empire find most surprising about the translation and interpretation professions in the 21st century ?

Elvin: Interpretation booths, consecutive note-taking with its plethora of symbols, distance interpreting, and of course, the fact that we don’t travel on horseback, since this was a mark of social standing in the Ottoman Empire.

- You can read The Role of Dragomans in the Ottoman Empire – in 19 languages and counting – on the AIIC Blog. Check in from time to time to see what new languages have been added… and if it hasn’t yet been translated into one of your languages, and you’re keen to make it happen, get in touch!

- We would like to express our gratitude to: Andrea Alvisi and Federica Mamini; Eleonora Barros; Burçak Fakıoğlu; Marie-Henriette Cassé and Sybelle Van Hal; Xu Chongtian; Katarína Chreňova; Marie-Madeleine Coulibaly; Florent Delany; Odina Diephaus; Zakia El Muharrifa; Marina Fayad and Maha El Metwally; Martina Fryda; Ephrem Houalakoue and Donatien Agbotoive; Tatiana Kaplun; Oqtay Kazimov; José Kikulu and Richard Muhungy; Dariga Kokeyeva; Beata Kubas-Lacka; Sirpa Lehtonen; Kimiko Monden-Bianchi; Majlinda Nishku; Alina Pelea; Sangwon Kim; Brana Sarkic; Haya Shavit-Kedar; Djibril Soumahoro and Ahmed Toure; Thu Do; Altantsetseg Tulgaa; Gregorio Villalobos; and Alexander Zaphirou.

Articles published in Communicate! reflect the views of the author(s) and should not be taken to represent the official position of AIIC.

Journeys

Wherever you go, there you are

Loin des yeux, loin du cœur

Quelques réflexions sur l'interprétation à distance

Testing... testing... 1,2,3

A Canadian assessment of RSI platforms

How can I make RSI platforms work for me as a freelancer?

The Business of Interpreting

The future is hybrid

A virtual discussion about the post-Covid landscape of meetings and events

“A complete and total game-changer”

ExCo reflects on 2020

Brokers and Heads of the Malabars

The search for Interpreter Zero

What is the Dragoman Challenge?

A multilingual journey of discovery (also in French)

India’s complex politics of multilingualism

Review of “Le métier d’interprètes en Inde"

Simultaneous simplification

A world first, to include people with intellectual disabilities

Image: Wikimedia Commons