History of the profession

Professional interpreters have always played an important part in international relations

The second-oldest profession

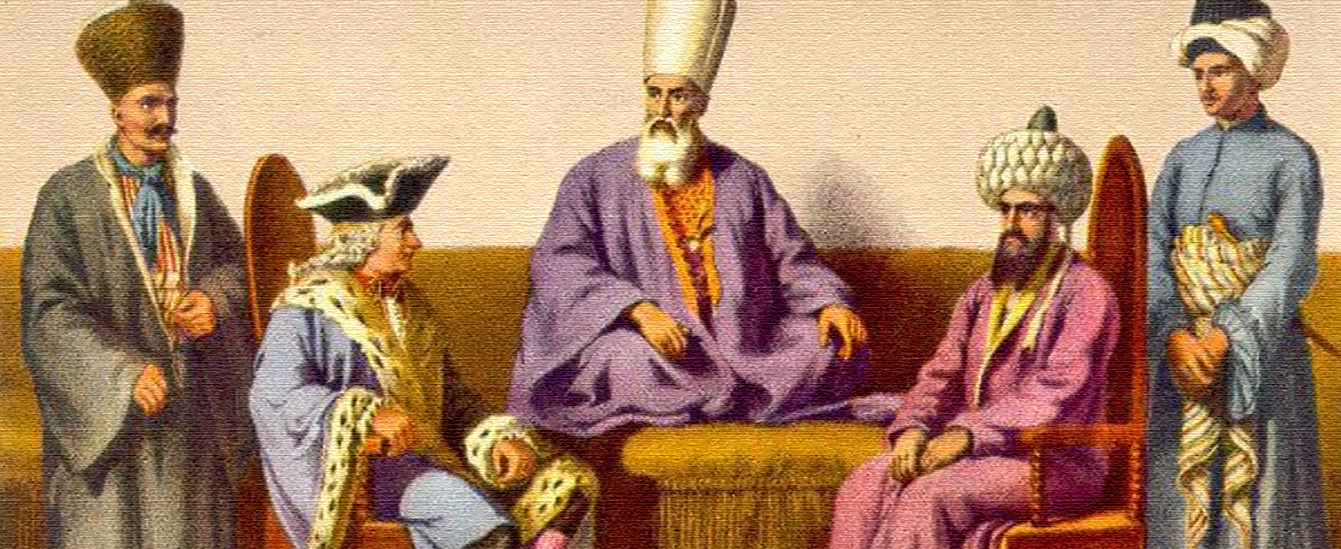

Throughout history, bilingual, intercultural or international negotiations and relations have involved interpreters – for so long, in fact, that accounts often omit them. Crusaders, explorers, conquerors, merchants, diplomats and others have always relied on intermediaries who could bridge linguistic and cultural divides. While there are records of early, self-described interpreters – in Byzantium, for instance, in England after the Norman Conquest or in the Ottoman Empire – these go-betweens were often co-opted into interpreting or did so because it fitted in with their other activities.

Languages of diplomacy

In medieval and renaissance western Europe, educated people were able to communicate in Latin, which was the language of international communication until well into the eighteenth century. It was subsequently supplanted by French until the early twentieth century.

Conference interpreting

When the Treaty of Versailles was negotiated after World War I, representatives of the UK and the United States preferred to speak English. As the meetings were conducted in English and French, they relied on interpreters. These early conference interpreters, men like Paul Mantoux and Jean Herbert, worked in consecutive interpreting mode. They were given the floor to interpret delegates’ speeches, putting themselves in those speakers ‘shoes’: these pioneers were the first conference interpreters.

The early international organisations, the League of Nations and the International Labour Office, initially used consecutive interpreting too. However, realising that consecutive took too much time with more than two working languages, the ILO started experimenting with simultaneous interpreting in the 1920s. In the 1930s, André Kaminker and Hans Jacob, two founder members of AIIC, also used a form of simultaneous to interpret Hitler’s speeches for French listeners.

The Nuremberg trials

It was at the historic trials of Nazi war criminals in 1945-46 that simultaneous interpreting as we know it today was used for the first time. Colonel Léon Dostert, who had interpreted for General Eisenhower, was responsible for making the arrangements. He introduced working arrangements that proved enduring: he decided that four teams of interpreters were needed, not only to interpret the proceedings with an unrestricted view of the courtroom, but also to observe the proceedings that they were not interpreting… and have some time off. There were also training opportunities for the many people working at the trials who were new to simultaneous interpreting.

─── 1945 and after

1945 and after

Conference interpreters played a significant role in the post-war period. While consecutive interpreting was still preferred for some meetings, the United Nations and its affiliated organisations decided to work largely in simultaneous. A new generation of interpreters gradually took over from the pioneers: men and women with multilingual backgrounds or who had chosen to study languages at school and university. Many of them decided to go one step further and undergo formal training in the increasing number of specialised interpreting schools.

─── Recognition

Recognition

The development of conference interpreting after World War II led to a recognition of the contribution made by interpreters to the growing number of international conferences, organisations, conventions and treaties. Their determination to ensure that this recognition translated into respect for the profession and solidarity within it culminated in the establishment of AIIC in 1953.

See also: History of AIIC

Photo: Wikimedia Commons