Brokers and Heads of the Malabars in 18th-century Pondicherry

Looking for Interpreter Zero - Episode 23

by Christine Adams – October 2020When a local resident appeared before the council, he usually spoke in Tamil, an interpreter translated the response aloud into Portuguese for the benefit of the French audience and officials, and a French (but Portuguese-speaking) secretary then wrote down the response in French. [1]

The predecessor of Ranga Pillai in the office of the Company's chief dubash and courtier at Pondichery. Dubash means literally " a man of two languages, " i.e., an interpreter. This was the original significance of the word, but at the time that the diary was written it was applied also to a native agent, or broker, who negotiated the purchase of merchandise. Hence the title courtier (broker) conferred by the French authorities on their chief dubash. [2]

But these were above all figures who, even if they acted at the behest and with the backing of powerful imperial systems, were heavily constrained in their actions, and thus caught as it were between a rock and a hard place. [3]

There are two buildings in Heritage Town in the former French colony of Pondicherry that are associated with men who were key to the success of French trade there: St Andrew’s Church, built in 1745 by Pedro Kanakaraya Mudaliar in memory of his son, and the 1735 house owned by Ananda Ranga Pillai, who succeeded Mudaliar as chief intermediary for the French. These rare remnants of the early colony point to the French architectural and religious stamp on the region as well as the way these Tamil men gained wealth and prestige by helping the outsiders with their trade.

Andrews Church Pondicherry (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

A French foothold

The French were relatively late in attempting to get a foothold in India through the Compagnie des Indes, founded in 1664. Their presence on the subcontinent was constrained geographically, which provides opportunities for a focused look at their relations with their intermediaries.

They first tried to set up a trading post in Surat in 1688 but it was too crowded for newcomers to make any headway. In 1674, Shar Khan Lodi, the governor of the Coromandel coast gave them Pondicherry, which became the capital of their Indian settlement of five trading posts. By 1715 there were some 2000 French settlers – in the French, or White Quarter - and tens of thousands of mostly Tamil-speaking inhabitants, many of them weavers, who contributed to the area’s trade in textiles. They lived in the Indian, or Black Quarter, now known as Heritage Town.

A new language for a new town

The name of the French settlement in Tamil, “Puducherry” means ‘New Town’. The Compagnie des Indes had the advantage of settling into new territory rather than negotiating for space in an established community. While they had the opportunity to impose their own laws and institutions there, they had to adjust to some long-standing trade practices, including the use of Portuguese as a lingua franca. The French traders needed

The officials sent from France needed intermediaries too, as did the missionaries; the Jesuits, Capuchins, and members of the Missions étrangères de Paris (MEP) all needed assistance in spreading the word - their interpreters were called catechists. The French thus provided opportunities for any number of interpreters working for traders, for the government or for the missionaries.… brokers who could serve as linguistic interpreters and were able to speak Portuguese with their French employer and Tamil, Telugu and Persian with their local connections [4]

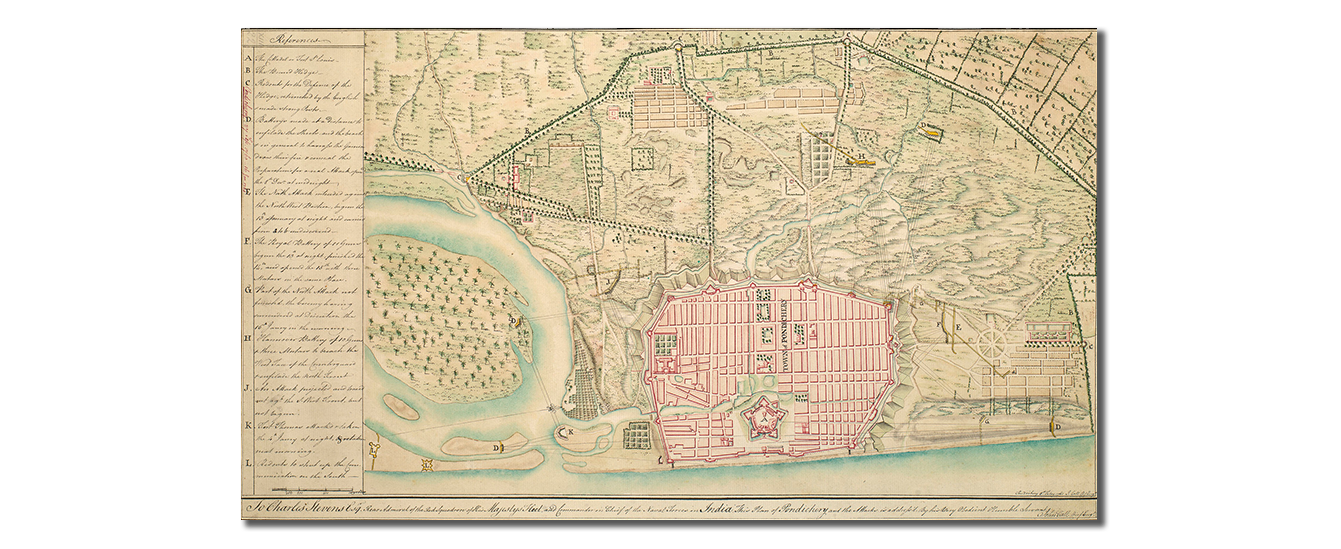

18th Century Pondicherry (Map from the Royal Collection Trust)

Le Courtier et Chef des Malabars

The Compagnie decided on a title for the official who was to represent them and act for them with local traders and suppliers: Courtier et Chef des Malabars (Broker and Head of the Malabars). The post involved acting for the French as a broker and requited someone with high status in the local Tamil community, referred to as “Malabars”, the term used by the French for people living in the southern part of the sub-continent.

The first Broker, Thanappa Mudaliar was an early convert to Christianity who moved to Pondicherry in 1674. He played a key role in helping the French deal with local traders and was instrumental in getting weavers to settle in the new town as well as overseeing the building of warehouses for goods to be shipped from there. His son André Muthappa Mudaliar succeeded him as chief broker in 1699. [5]

Nayiniyappa: Indispensable… and successful

Another ambitious young man moved to Pondicherry from Madras in 1674: a young Hindu, Nayiniyappa. He also wanted to work with French traders by helping them deal with local producers. He made the practical decision to find a place in the local community by working at the civil court (Chaudrie) as an interpreter.

The intimate connection he could have forged with French traders as he whispered into their ears in Portuguese would have cemented his position as a man to be trusted. Working in the Chaudrie as an interpreter would also have fortified his place among the town’s Tamil population, as a man directly involved in the settlement of disputes. [6]

Nayiniyappa thrived in Pondicherry. In 1704 he was awarded the right to farm tobacco and betel leaf for two years and in 1708 he was appointed Courtier et Chef des Malabars by Governor Hébert. There were objections from the Jesuits that he was not Christian but they did not manage – then – to have him denied the office. His success in the colony was such that the lavish celebration of his son’s 1714 wedding took up several pages of an incoming French ship captain’s diary. Here was an intermediary who had made himself indispensable and wealthy in the service of the French.

Nayiniyappa’s nephew Ananda Ranga Pillai’s diaries from the years 1736 to 1761 give a good idea of the responsibilities involved. The introduction to the English translation of the fourth volume of the diaries gives this job description:

As the principal factotum of the Governor, he was expected not only to assist in the negotiation of the Company’s investment and the provision of the Governor’s private trade, but also to procure intelligence, to advise concerning political relations with the country powers, to see that the Governor’s correspondence with them was properly interpreted, to arrange for the offering of suitable presents to the Governor on the proper occasions, to conduct intrigues in which the Governor wished to avoid personal intervention, to watch, report, and advise on the state of public feeling among the Indian inhabitants. [7]

Nayiniyappa’s golden years lasted until 1716. He came to spectacular grief when Hébert returned to reclaim the role of governor after having been removed from office in 1713.

Fall from grace

In February 1716 Hébert had Nayiniyappa arrested and charged with both sedition and tyranny, implying opposition to French authority and abuse of his own power. It is difficult to establish the reasons for the broker’s fall from grace. With respect to the first accusation. it was felt that he had been on the wrong side of a dispute between the French authorities and Hindu weavers, labourers and traders who had threatened to leave the town in 1715 to protect their religious freedom. Then he was accused of mocking the poor of Pondicherry, many of whom were Christian, by inviting them to his home in February 1715 for gifts of food, cloth, and rosaries. The Jesuits had long argued for the influential post to be held by a Catholic and Hébert may have had his reasons for siding with them. Danna Agmon’s book A Colonial Affair deals admirably with the complexities of this case. [8]

The way Hébert dealt with the language arrangements for the investigation of his chief broker, with whom he had always spoken Portuguese is a clear indication that this was a show trial. All of the court’s – the Conseil Supérieur’s – dealings with Nayiniyappa were held in French and Tamil. The colony’s communicator-in-chief, who had always worked in Portuguese and Tamil, had to reply to questions put to him in French and interpreted into Tamil by Manuel Geganis, the son of a Jesuit catechist who had worked for the Compagnie and the Jesuits. Here we have the paradox of an interpreter being provided in order to intimidate and prevent communication. There was little intention of giving Nayiniyappa a fair hearing. He died in prison in 1717 while serving a three-year sentence after having been subjected to a public whipping and had his property confiscated.

Beating them at their own game

Thanappa Mudaliar’s grandson, Pedro Kanakaraya Mudeliar, was appointed acting Broker when Nayiniyappa was arrested. He was Christian, so the Jesuits felt that the Compagnie was finally listening to them. However, the story did not end there. In a clear indication that ambitious middlemen can play their interlocutor’s game, Nayiniyappa’s family challenged the court’s decision by appealing to the Conseil, the King, and the Naval Council. Not only was Nayiniyappa’s conviction overturned and Hébert arrested but the family was granted reparations in 1720.

Nayiniyappa’s oldest son, Guruvappa, sailed to Paris after his father’s death. He was baptised while he was there, and returned home as Charles Philippe Louis Gourouapa, having been made a knight of the Order of St Michel. On his return, he was made chief broker, a position he held until he passed away in 1724. He was succeeded by Pedro Kanakaraya Mudeliar who served until his death in 1746, when the position was taken by Nayiniyappa’s nephew Ananda Ranga Pillai. Pillai’s Pondicherry house still stands and his diaries provide a wealth of information, both flattering and not, on trade and life in general in the colony.

Bust of Pedro Kanakaraya Mudaliar (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Between a rock and a hard place

Pillai gives an anecdotal account of the Broker’s responsibilities while relating a conversation with one Ramachandra Aiyan about why Mudeliar’s brother, Chinna did not get the job:

"Chinna Mudali will never get the appointment. He is not fit for it. When he was interpreter of the court he was guilty of many misdeeds. He took bribes of one cash and upwards. Besides, the Governor has called him a donkey. So say all the other Europeans. For these reasons, he will never get the place."

"But I have another communication to make to you," he continued; "and it is this : The Governor has said, in the presence of all the other Europeans, that you are the only person fitted for the post, and that he is determined to give it to you.” [9]

Go-betweens depend on the other parties; those who worked with the French in the early days of their presence in Pondicherry were undoubtedly “heavily constrained in their actions, and thus caught as it were between a rock and a hard place” [10] ; sometimes, however, they gained the upper hand.

The long association of two families with the French authorities in Pondicherry shows that intermediaries could benefit from imperial presence. The French depended on them and they gained from their proximity to power, as their legacy in the old Pondicherry Ville Noire shows: there is a bust of Pedro Kanakaraya in St Andrew’s Church;and Ananda Ranga Pillai’s descendants live in his house on Ananda Ranga Pillai Street – both buildings stand as rare monuments to intermediaries who are all too often forgotten.

- See also Looking for Interpreter Zero: Imperial Intermediaries III (including a list of all previous episodes)

- Looking for Interpreter Zero will soon have its own home at interpreter-zero.org – watch this space for the complete series!

Notes

[1] Agmon, D. 2007. A Colonial Affair: Commerce, Conversion and Scandal in French India. Cornell University Press.p. 81.

[2] Dodwell, H. ed. 1922. The Private Diairies of Ananda Tanga Pillai Asian Educational Services, New Delhi, Chennai, Kolkata. Vol I p. 3.

[3] Subrahmanyam, S. Between a Rock and a Hard Place Some Afterthoughts pp.429-440, p. 440.

in 2009 Schaffer, S., Roberts, L, Raj, K, and Delbourgo, J. eds. The Brokered World: Go-Betweens and Global Intelligence, 1770-1820.

[4] Ibid p.79.

[5] Wikipedia https://bit.ly/2VyYett

[6] Agmon, op cit p. 80.

[7] Dodwell, op cit. Vol IV p. iv.

[8] Agmon, op cit.

[9] Dodwell. p, 388.

[10] Subrahmanyam, op cit.

Articles published in Communicate! reflect the views of the author(s) and should not be taken to represent the official position of AIIC.

Journeys

Wherever you go, there you are

Loin des yeux, loin du cœur

Quelques réflexions sur l'interprétation à distance

Testing... testing... 1,2,3

A Canadian assessment of RSI platforms

How can I make RSI platforms work for me as a freelancer?

The Business of Interpreting

The future is hybrid

A virtual discussion about the post-Covid landscape of meetings and events

“A complete and total game-changer”

ExCo reflects on 2020

Brokers and Heads of the Malabars

The search for Interpreter Zero

What is the Dragoman Challenge?

A multilingual journey of discovery (also in French)

India’s complex politics of multilingualism

Review of “Le métier d’interprètes en Inde"

Simultaneous simplification

A world first, to include people with intellectual disabilities

Photo credits